Typically, our beliefs manifest in our verbal and non-verbal behaviour. If I believe that it rarely snows in London, I am committed to the truth of the claim that it rarely snows in London. Thus, a belief is a mental state that purports to represent reality. First, what is a belief? Whereas our desire tells us how we would like things to be, our belief tells us how we take things to be. Let’s see what it means for a delusion to be a belief that is epistemically irrational.

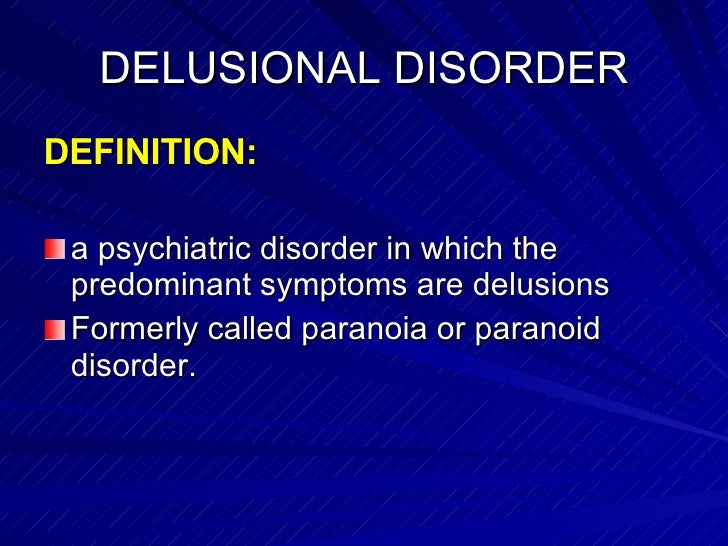

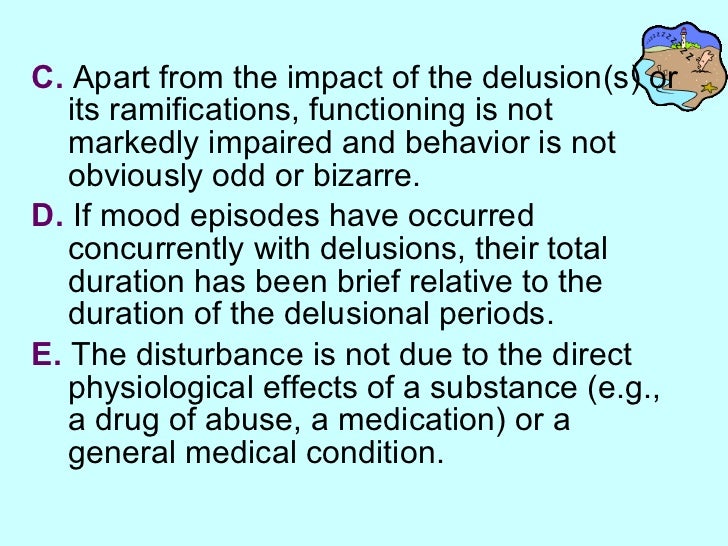

Of the delusions, and identify delusions as epistemically irrational beliefs. I argue that the study of delusions has contributed to challenging some widely accepted assumptions in the philosophy of mind concerning the relationship between epistemicĪlthough definitions of delusions vary to some extent, most definitions are based on the surface features A careful analysis of the results of focused empirical work on the relevant phenomena, and attention to detail in the relevant case studies can reveal the inadequacy of established philosophical theories and suggest new ways of looking at things. As I hope to show, there are opportunities for philosophers who engage in interdisciplinary projects to learn something from the empirical and clinical sciences about the nature of those phenomena that have traditionally been at the centre of philosophical investigation. In this chapter, I want to focus not on what philosophy can do for psychology and psychiatry, but on what psychology and psychiatry have done for philosophy. Philosophers can also help develop a field in a certain direction, offering hypotheses to test and examining the wider implications of existing empirical results. However, as others have observed (e.g., Fulford, Stanghellini, & Broome, 2004), the role of the philosopher does not need to be so narrowly confined. By all means, such roles are important and philosophers are well placed to assist. In discussions about interdisciplinary projects involving philosophers, it is not uncommon to identify the role of the philosopher with the conceptual tidying up and clarifying that are often deemed to be necessary in complex empirical investigations, or with the capacity to place a timely investigation within a wider historical context. This suggests that epistemic irrationality cannot account for the pathological nature of delusions. Yet, they are very common and widely regarded as adaptive

Optimistically biasedīeliefs about ourselves, for instance, may also be poorly supported by the evidence available to us, and resistant to the evidence that becomes available to us at a later stage. Third, beliefs exhibiting the features of epistemic irrationality exemplified by delusions are not infrequent, and they are not an exception.

Sometimes, an epistemically irrational belief has some long- or short-term epistemic benefit because it shields us from anxiety or supports our sense of agency. Second, our beliefs do not need to be epistemically rational to have a positive impact on our psychological wellbeing or understanding. The ascription of an epistemically irrational belief to us often contributes to the process of explaining and predicting what we do. What do we know about delusions that can inform our understanding of how beliefs are adopted and maintained, and how they influence behaviour? What have philosophers learnt from delusions? An entire volume could be dedicated to this issue alone, but in this chapter I will focus on three core philosophical claims about epistemically irrational beliefs that our knowledge of delusions have successfully challenged.įirst, our beliefs do not need to be epistemically rational to be used in the attempt to interpret our behaviour. In recent years, the focus on delusions in the philosophical literature has contributed to dispel some myths about belief, making room for a more psychologically realistic picture of the mind.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)